EFHA World 26.03.2023

08.09.2022

designfashion designItalian fashionperformanceTales from the archivetheatre

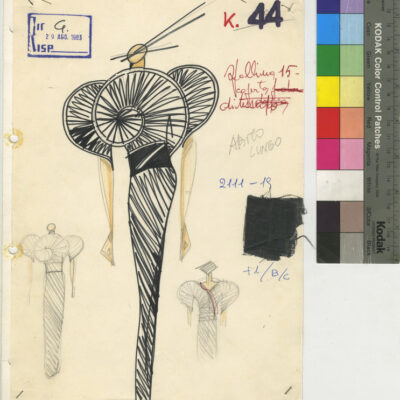

In occasion of “Cinzia says…”, the first major retrospective of Italian artist and fashion designer Cinzia Ruggeri, here is the second guess post by Dr Elena Fava on Ruggeri’s performative designs

Cinzia Ruggeri considered dressing as an intentional gesture to stage oneself. The spectacular and performative component pervaded all the designer’s projects, overcoming the distinction between real and fictional clothes. The physical and sensorial qualities of her designs turn them into perfect props, whose expressive potential unfolds when worn on stage. The real engine activating the connection clothes have with the world is, indeed, the female body.

Her collaboration with the theatre therefore seems natural. Between the late 1970s and early 1980s, Ruggeri designed costumes and sets for Valeria Magli, a dancer forged by philosophical studies, inspired by the work of contemporary choreographers and poets, and dissatisfied with the common perception of the relationship between femininity and creative action. The ‘use’ of her body became the centre of her own research in these years, when she was deemed ‘inventor’ of the so called poesia ballerina. Magli’s poesia ballerina was a stage practice that wove together dance and poetry, creating a plot through movement, putting into play the original relationship between the two idioms.

When on stage, Valeria Magli performed an ideal body through her body in the space of the scene, expanding the expressive possibilities offered by poetry, music and images. In the same years, the second Italian verbovisual avant-garde experimented with poetic action and performances. Her research, exploring the shared territory between body and performance, allowed her on the scene to give visible form to feminist stances, above all declaring a proud feminine identity in an artistic environment – the Italian theatre scene – mainly operated and managed by men.

Cinzia Ruggeri’s performative dress and Valeria Magli’s poesia ballerina found a common scene on the stage of the Teatro di Porta Romana in Milan. In the 1980s, the theatre served as the laboratory for two distinct femininities in definition, different but both germinated by reflection on the body and comparison with the avant-garde and with the neo-avant-garde.

The collaboration between Magli and Ruggeri started in December 1979 with Schönberg Kabarett (Bologna, Teatro San Leonardo, 1979), and continued with Indications de jeu[1], a project, presented for the first time within 24h Satie, a 24-hour marathon of shows dedicated to the French composer. The dancer interpreted the text of Erik Satie Le pourteur de grosse pierreswhich Nanni Balestrini indicated as a reference for the choreography of the performance. The main theme of the action was the contrast between appearance and reality. The only elements on the scene were a large pumice stone made of polystyrene and Magli’s body; with studied gestures, the dancer seemed to transform the material of the stone from heavy to very light, eventually revealing the perverse game of material illusion.

The two projects that best summarize the artistic dialogue between Cinzia Ruggeri and Valeria Magli are Banana morbideand Banana lumière. Although conceived at different times, the two plays were presented together in a single show, divided into two complementary acts.

Banana morbide was played on the claquette, and, as Magli said, it was the body that produced the sound though movement:

[…] tip-tap as a web of sounds, rhythmic path, sound body. Not only a forerunner, a musical film, but a backward glance at the primitive dances, the beating of the foot on the ground […] Banana and soft, rigid and sinuous, hard and soft, soft by assonance [‘morbido’ means ‘soft’ in Italian] and morbid by meaning, a seamless path between masculine and feminine, between exchange, interaction, opposition, parallelism. (Valeria Magli, 1980)

The performance was a refined interpretation of tap-dance performed on evocative texts by Nanni Balestrini and music without melody by John Cage. It was the action of dressing in tinted and transparent veils that transformed the performance from the silly dance of a girly ‘soubrettina’ into a cold and cerebral reverse striptease. The erotic potential conveyed by the minimalist scenography – a black and white piece of fabric, crossed by a red tongue that unrolls up to the front row – was diluted and even repressed by a storyline that had no crescendo, but instead used dress to perform a caustic and cruel game of exhibiting the female body essentially by veiling it. The scene and costumes created by Ruggeri transferred the idea of a performance dress to the stage and became pivotal elements of both the choreography, at the level of poses and gestures, and of all the narrative action of the play.

Even in Banana lumière the costumes visually marked a kind of change. While for Banana morbide the act of dressing in the performance conveyed a change in the perception of the female body from one ideal to another, Banana lumière’s plot revolved around the transformation of the body of the dancer from human to object, more precisely, to a mobile.

In particular, the black jumpsuit seemed conceived as to annihilate the volume of the body, while the decorations that interact with Piero Fogliati’s ‘fantastic lights’ turned the movements of the dancer in abstract figures. A similar tribute to Futurist experiments can also be found in the kinetic decorations that, in the same years, Ruggeri introduced in the suits she designs for her brand Cinzia Ruggeri. More generally, these costumes / clothes appeared as a material reflection on the language and on the spectacular nature of the historical avant-garde, an aspect that in the postmodern debate normally remains subordinate to the analysis of the critical meanings of the operations.

The Teatro di Porta Romana brought together two complementary ideas of femininity: sophisticated and ironic for Ruggeri, committed and cultivated for Magli. The encounter reinforced individual researches and activated a collaboration between the two authors, with the aim of targeting the space of the scene.

The fashion designer further developed experimental solutions conceived for theatrical costumes in her prêt-à-porter collections, for example by creating Abito muretto (S / S 1983 collection) where real flowers could grow. Vice versa, some models of the Bloom line – designed for their commercialization – were then adapted to dress the mysterious Signorina Richmond, performed on the stage of the Porta Romana from 1980; the famous Abito di luci a 12 watt (S / S 1982 collection) was chosen by Magli to interpret John Cage’s Sixteen dances, illuminate with a touch the black uniforms of the members of Milan Conservatory in 1985.

The collaboration stretched beyond the stage at Porta Romana, and explored other territories, at times more familiar to Ruggeri: as, for instance, the video Per un vestire organico, a project by Ruggeri developed in December 1983, which sees Magli as main interpreter.